Safeguarding Constituent Information

BY ANNE MEEKER

Introduction

Constituents often provide Members of Congress and casework teams with highly sensitive personal, financial, medical, immigration, and criminal justice information in the course of casework interactions.

While the legislative branch exempts itself from many laws around privacy and government information, Members of Congress and casework teams have an important ethical obligation to handle constituent data responsibly, keeping it safe from exposure, loss, or theft.

This chapter explores the procedural landscape around data for Congress, best practices for safeguarding constituent information in normal casework, and some above-and-beyond recommendations for demonstrating to constituents that your office is a trustworthy steward of their sensitive information.

Understanding the Privacy and Data Landscape for Congress

Agencies require a Privacy Act Release Form (PF, PRF, or PARF) to ensure that individuals have given permission for the Congressional office to act on their behalf, in accordance with the Privacy Act of 1974. This law “establishes a code of fair information practices that governs the collection, maintenance, use, and dissemination of information about individuals that is maintained in systems of records by federal agencies.”

The Privacy Act mandates that federal agencies cannot release personal information pertaining to an individual without that individual’s written consent, and creates rules around how agencies may store data and how individuals may request that data.

There are some exceptions: the Privacy Act includes twelve exemptions to information that can be released without written consent. Most of these involve routine, non-identifiable data, but the ninth exception is about Congress:

No agency shall disclose any record which is contained in a system of records…except pursuant to a written request by, or with the prior written consent of, the individual to whom the record pertains, unless the disclosure would be—

to either House of Congress, or, to the extent of matter within its jurisdiction, any committee or subcommittee thereof, any joint committee of Congress or subcommittee of any such joint committee.

5 U.S.C. § 552a(b)(9).

The Privacy Act & Data Ownership

Since this law was passed, case law has clarified that this exception does not apply to inquiries made by Members of Congress on behalf of individual constituents. This is why offices must have a signed Privacy Act Release Form to allow agencies to disclose information to casework staff.

However, this law (and others like it, including the Freedom of Information Act, or FOIA) apply only to Federal agencies¹—not to Congress. Members of Congress are not restricted by the Privacy Act with regard to how they can handle or disclose constituent information.

In fact, all information constituents provide to their Member of Congress is considered that Member’s personal property. Constituents have no legal say in how their information is handled once it is given to their Member of Congress, and no legal rights to request copies of that information or have their preferences for its disposal followed.

This data ownership is especially important in transfers between Members of Congress: when a Member retires or loses an election, they have full control over how their constituents’ information is handled, whether that means it is transferred entirely to the incoming Member, transferred partially, or destroyed. House and Senate Ethics manuals provide information on restrictions on data elements like campaign databases, or using non-official funds to transfer data on non-official devices, but they provide little guidance on the use and safeguarding of constituent information obtained in the casework process.

Best Practices on Constituent Data

In comparison to restrictions on federal agencies and other levels of government, this affords considerable leeway for Members in handling sensitive information. However, with constituents increasingly aware of the risks of insecure data handling, it is also an opportunity for offices to stand out by developing best practices and internal rules pertaining to how they will act as responsible stewards of constituent data.

As with an office’s physical security, auditing and developing responsible practices for digital security starts with assessing risk: what kinds of information are sensitive, what kinds of dangers do they face, and how can those risks be mitigated?

Physical Document Handling

Documents that pose a risk are documents with sensitive constituent information: this includes personally-identifiable information (or PII), health information, and financial information. The Department of Labor defines PII as:

Information: (i) that directly identifies an individual (e.g., name, address, social security number or other identifying number or code, telephone number, email address, etc.) or (ii) by which an agency intends to identify specific individuals in conjunction with other data elements, i.e., indirect identification. (These data elements may include a combination of gender, race, birth date, geographic indicator, and other descriptors). Additionally, information permitting the physical or online contacting of a specific individual is the same as personally identifiable information.

The vast majority of documents accessed in the casework process — including health records— fall into this category.

Paper vs. Digital

Even as the world becomes increasingly digital, casework still involves so much paper, from physical Privacy Act Release forms to physical copies of agency letters, military records, medical records, tax documents, and more. The good news is that the House Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress recently made a related recommendation:

To help streamline casework requests and help constituents better access federal agencies and resources, the House should implement a secure document management system, and provide digital forms and templates for public access.

With the creation of the new House Digital Service under HIR, and the relative success of digital Privacy Act release forms available to the House and Senate, there is a chance that digital casework solutions may be implemented in the near future, and would bring down the total volume of documents caseworkers have to handle in physical copies or over email.

Safeguarding Physical Records

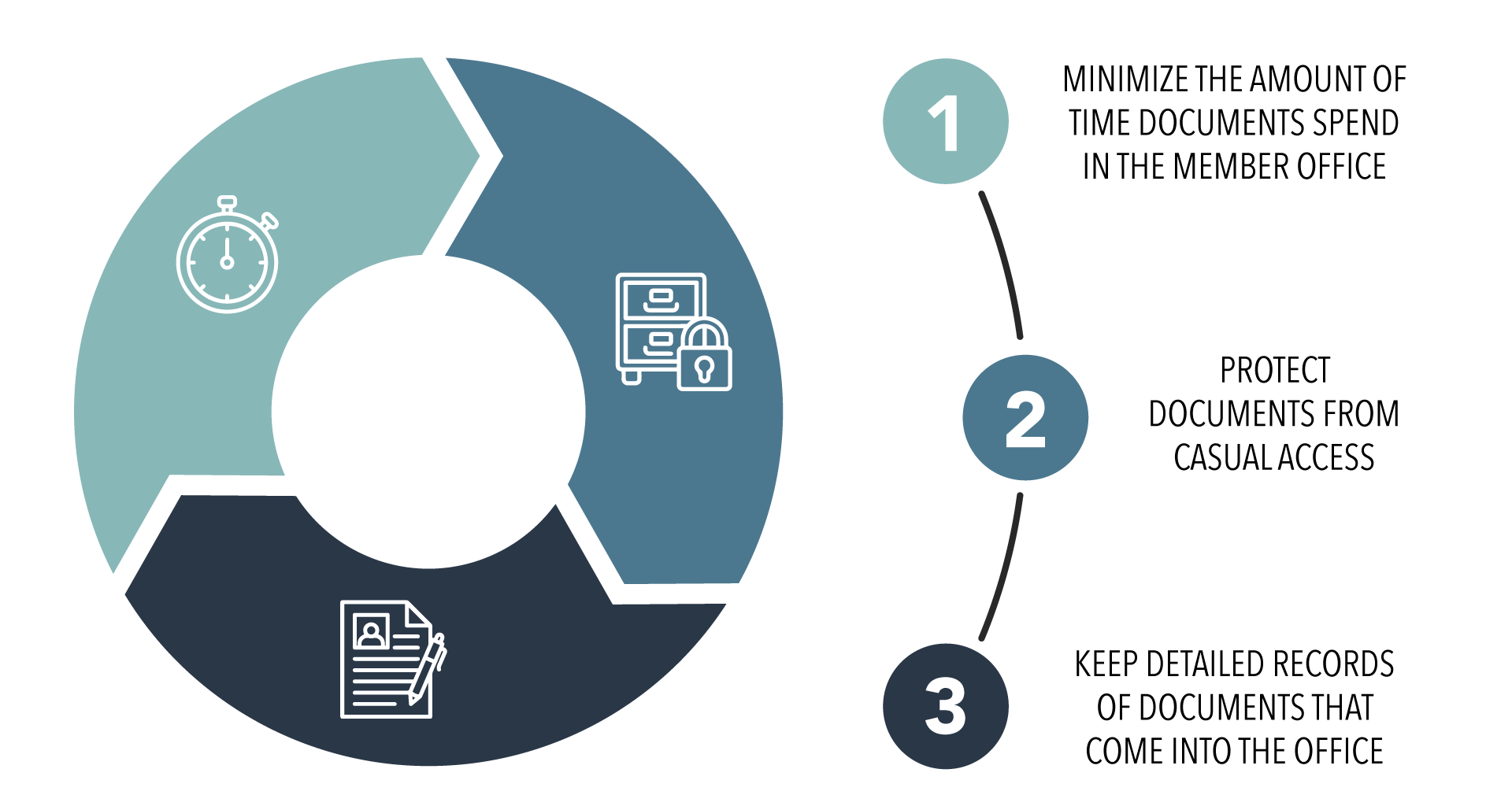

However, for now, physical documents in Congressional offices remain vulnerable to theft, loss, and damage. Safeguarding physical records comes down to three principles:

1. Minimize the amount of time documents spend in the Member’s office

The more time a document spends in the Member office, the more risk the team assumes for that document’s handling. The goal for a document-handling process that minimizes risk should be for the office to possess the physical copy of that document for as little time as possible.

Safe options for disposing of documents after scanning and uploading them to digital systems are only:

Shredding the document, or

Returning the document to the constituent.

Congressional offices should decide how long to keep documents on premises: for example, one goal could be to keep physical documents no longer than 24 hours, or another could be to clear out all physical documents on the premises by 4 PM every Friday.

2. Protect documents from casual access

One risk to sensitive documents is leaving them out in the open where they can be seen at a quick glance. Casework teams should establish a system in which documents not being actively worked on are covered to keep them safe from view: for example, designating a particular folder or binder as the “intake file” (possibly with the document log attached; see below) where documents coming into the office are placed before they can be filed.

If the team decides to keep some documents on the premises (for example, a document that comes in at 4:59 PM when the team is getting ready to leave, or documents that the caseworker plans to include in a mailed packet in the next few business days), arrangements should be made to secure those documents, for example in a locked filing cabinet.

3. Keep detailed records of documents that come into the office

One of the worst things to hear from a constituent is “I already gave you that document.” To build trust and stay organized, keeping detailed records of the physical documents that come into the office is key.

This may include a physical log or a shared spreadsheet using a platform like Airtable or Google Sheets to track each incoming document:

Case the document is associated with

Name of the document (as labeled in your office’s CMS)

When did it come into the office

How did it come into the office (walk-in, mail, fax)

Who handled it

How many pages did it include

Did it contain PII/HIPAA/other sensitive information

Confirm it was uploaded to the constituent’s case in your office’s CMS, or included in your office’s intake process or emailed to the appropriate caseworker if there is no case open

How was it handled afterwards (this will depend on your process—options include frank mailed back to the constituent if original or shredded if a copy, or placed in your office’s secure area for documents that have to be kept in hard copy)

Since interns will be the primary point of contact for handling documents, training each new intern class in these three principles and the team’s process to properly handle documents is critical.

Casework teams are strongly encouraged to establish a standardized system for labeling documents in constituent cases. For example, one option could be “constituentlastname_threewordsummary_documentdate” (ex. “jones_dd214_1987feb6).”

Screen Access & Remote Casework

The ability to work remotely by logging into CMS systems via a VPN is a game-changer for good casework: not only does it keep the team flexible in case of emergencies, but it also lets teams blur the lines between casework and outreach, going out into the community to meet constituents where they are.

However, working with a CMS system in public also poses risks: sensitive constituent information may be visible on screen, or constituent documents may be handled in public.

Some steps to protect constituent information in public are common sense:

Staffers should sit with their back to a wall to keep someone from seeing the screen

If a computer or tablet must be left for a moment, the staffer should log out of their VPN and lock the device

Staffers should never share passwords or passcodes for the device unless absolutely necessary

Phone calls in which sensitive constituent information is discussed should be kept to a minimum outside of the office.

Several small pieces of equipment can help keep constituent information safe on the move:

A small portable scanner can plug into laptops to allow for scanning documents on the spot. Good versions start around $80, and will prevent the need to accept physical copies of sensitive information.

A screen privacy filter that keeps screens from being seen by anyone not sitting directly in front can further secure access to devices.

Digital Use & Privacy

The House firewall (the network used to access office CMS systems and Housenet or Webster) is very secure. While email is slightly less preferable for sharing important documents than a secure dedicated file-sharing software, for the most part, caseworkers and constituents can feel confident knowing that information behind the House firewall is safe.

However the safety of any system is dependent on its users. All staffers handling constituent information should complete cybersecurity training on time, and take responsibility for making sure that interns do the same.

If offices use a file-sharing service like Google Drive or Microsoft OneDrive, or an office-wide messaging service like Slack, it is important to avoid uploading constituent documents to either of these.

Each of these components of constituent information security should also be a standard part of onboarding for interns and all new staff who may interact with constituents.

Above and Beyond Options

As discussed, constituents have no legal rights with regard to information they provide to their Members of Congress. However, many Members may feel that it is appropriate to voluntarily offer constituents additional information, or opportunities to express preferences about how their data will be handled that Members agree to abide by. The section below offers starting points for Member offices who would like to go above and beyond to prioritize constituent input and wishes in how sensitive casework data is handled. These recommendations are voluntary, and should be developed in collaboration with office leadership.

Offer Additional Information in PARF

Standard language on digital Privacy Act Release forms, used by most House and many Senate offices, is as follows:

To be able to assist you, we must have a signed privacy release form that clearly outlines your problem and the remedy you are seeking. By checking the box below you are giving our office permission to look into the matter on your behalf. Please make sure to attach below any relevant identifying information and supporting documents which relate to your inquiry. [...] I hereby request the assistance of the Office of [...] to resolve the matter described below. I authorize the Office of [...] to receive any information that they might need to provide this assistance. The information I have provided to the Office of [...] is true and accurate to the best of my knowledge and belief. The assistance I have requested from the Office of [...] is in no way an attempt to evade or violate any federal, state, or local law.

It is notable that this standard language does not make it clear to the constituent that the information they provide to their Member of Congress in the course of their case is the personal property of the Member, to be used, transferred, or disposed of at their discretion.

An office may opt to include short language on their office’s Privacy Act release form page (either directly on the page or linked in a “more information” page) with information on what the release form specifically authorizes (i.e. federal agencies to disclose information to the listed Congressional office), and how constituent data provided to the office in casework is used at the Member’s discretion.

While disclosing this information may make some constituents less likely to pursue casework, it provides constituents with the opportunity to make an informed decision about how their information will be used. Any potential changes should be discussed with office leadership and potentially reviewed by counsel to ensure that it accurately reflects the office’s policy.

Offer Constituent Preference on Casework Data in Congressional Transitions

An additional step, in conjunction with the information above, would be to offer constituents a choice for how their data will be handled if/when their Member of Congress leaves office.

This could take the form of a checkbox on the Privacy Act Release form, or in a form letter when cases are closed where the constituent can express a preference for whether their case data may be transferred to a new office or deleted.

Again, it is advisable that offices consult an attorney on the wording of this form, and/or note that the office will do their best to follow the constituent’s expressed preference, but that compliance is voluntary, and offices will follow guidance from Ethics and counsel in making decisions.

For many constituents, this decision will change depending on whether their case is open or closed, as well as on the specific circumstances of a case transfer (i.e. who wins the Congressional seat). A casework team may decide that it will also make sense to ask constituents to re-authorize transfer or deletion at the end of the Member’s term, for example by sending all constituents with open and/or closed casework an opt-out letter where they have the choice to opt out of having their data transferred to an incoming Member.

Teams can work with CMS vendors to develop specific case tags that track a constituent’s preferences: for example, “TRANSFER_AUTH” OR “NO_TRANSFER” to make it easy to pull lists of constituents for your CMS vendor in the chaos of a transition period.

Customizable Templates

Privacy Act Release Form Info + Preference

What is this form?

The Privacy Act of 1974 mandates that federal agencies cannot release personal information on a constituent without that constituent’s written consent, and creates rules around how agencies may store data and constituents may request that data. While Congress has a blanket exemption to the Privacy Act for obtaining agency information necessary for legislating, individual constituents’ information is not covered by this exemption. This means that federal agencies cannot disclose your information to our team unless they have your written permission to do so. This form gives agencies we may work with permission to discuss your case with our team.

Information you provide to a Member of Congress is stored and used at the discretion of that Member. If and when [MEMBER] leaves office, to ensure continuity of service for constituents of the [STATE/DISTRICT], [MEMBER] may transfer information used in correspondence and casework to the incoming Member.

Our office will follow all current and future guidance from the House/Senate Committee on Ethics, Committee on House Administration/Senate Rules Committee, and House/Senate Counsel regarding how constituent data is handled. However, as far as possible, our team would like to respect your preferences for how your information is transferred.

Please let us know if you would like your information to be transferred to the next Member to represent [STATE/DISTRICT].

End-of-Congress Data Transfer Letter

Dear [Constituent],

As I reach the end of my tenure as your [Senator/Representative] for the [district/state], I wanted to say a sincere thank you. It has been the great honor of my life and my pleasure to serve on your behalf, and I could not be prouder of what we’ve accomplished together.

Through the end of my term, my first priority will be making sure that [INCOMING MEMBER] can hit the ground running to provide you with uninterrupted support and service as your voice in the federal government. This includes ensuring that [INCOMING MEMBER] has access to my office’s records.

To ensure continuity of service for constituents of the STATE/DISTRICT, my team will default to transferring all constituent data to NEW MEMBER. This includes records of correspondence, contact information, and any casework records.

If you would like to opt out of having your records transferred to your new Representative, please [INSTRUCTIONS]. If you have already expressed your preference for opting out of a transfer, there is no need to [INSTRUCTIONS] again.

If you have questions about your data and Congress, please see our [FAQ page], and contact our office with any questions.

Thank you again for the privilege of serving on your behalf.

[Member]

¹ Or, in the case of HIPAA, covered medical entities like doctors and health insurance plans